Wikipedia defines cryptography as “the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of third parties called adversaries”. However, I think a better definition would be:

Cryptography is about replacing trust with mathematics.

After all, the reason we work so hard in cryptography is because a lack of trust. We wouldn’t need encryption if Alice and Bob could be guaranteed that their communication, despite going through wireless and wired networks controlled and snooped upon by a plethora of entities, would be as reliable as if it has been hand delivered by a mailman letter-carrier as reliable as Patti Whitcomb, as opposed to the nosy Eve who might look in the messages, or the malicious Mallory, who might tamper with them. We wouldn’t need zero knowledge proofs if Vladimir could simply say “trust me Barack, this is an authentic nuke”. We wouldn’t need electronic signatures if we could trust that all software updates are designed to make our devices safer and not, to pick a random example, to turn our phones into surveillance devices.

Unfortunately, the world we live in is not as ideal, and we need these cryptographic tools. But what is the limit of what we can achieve? Are these examples of encryption, authentication, zero knowledge etc.. isolated cases of good fortune, or are they special cases of a more general theory of what is possible in cryptography? It turns out that the latter is the case and there is in fact an extremely general formulation that (in some sense) captures all of the above and much more. This notion is called multiparty secure computation or sometimes secure function evaluation and is the topic of this lecture. We will show (a relaxed version of) what I like to call “the fundamental theorem of cryptography”, namely that under natural computational conjectures (and in particular the LWE conjecture, as well as the RSA or Factoring assumptions) essentially every cryptographic task can be achieved. This theorem emerged from the 1980’s works of Yao, Goldreich-Micali-Wigderson, and many others. As we’ll see, like the “fundamental theorems” of other fields, this is a results that closes off the field but rather opens up many other questions. But before we can even state the result, we need to talk about how can we even define security in a general setting.

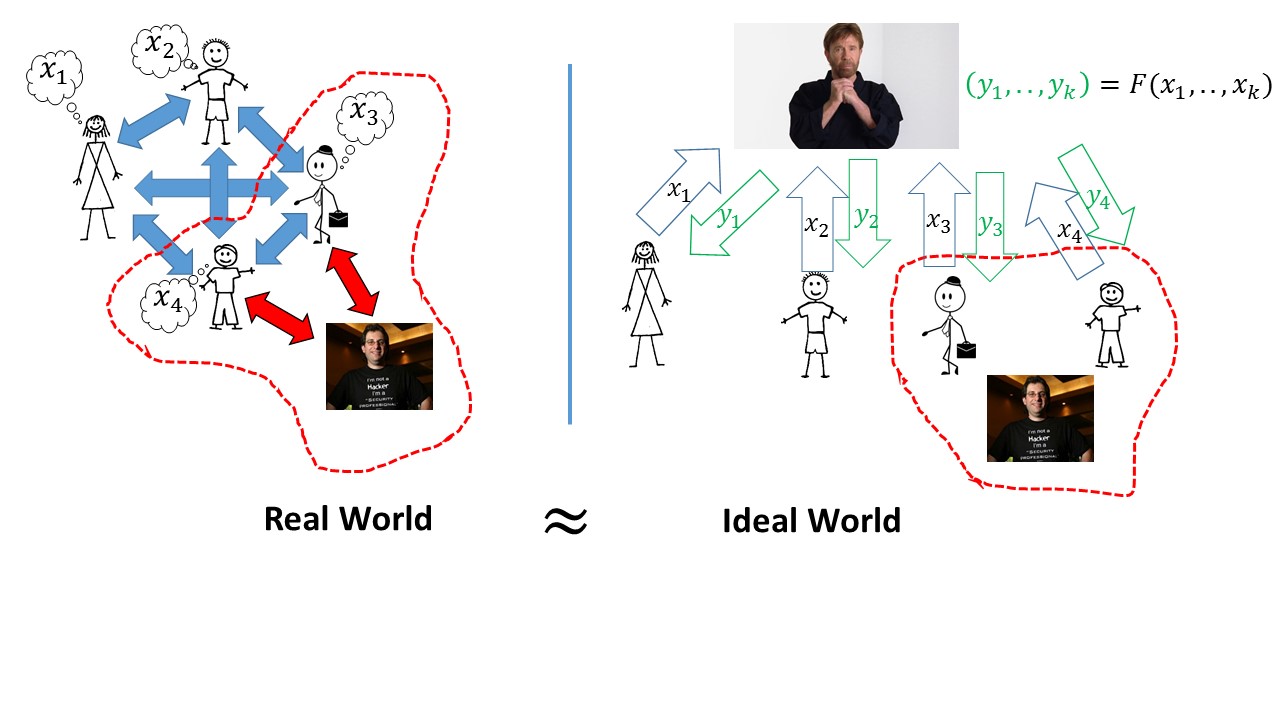

Ideal vs. Real Model Security.

The key notion is that cryptography aims to replace trust. Therefore, we imagine an ideal world where there is some universally trusted party (cryptographer Silvio Micali likes to denote by Jimmy Carter, but feel free to swap in your own favorite trustworthy personality) that communicates with all participants of the protocol or interaction, including potentially the adversary. We define security by stating that whatever the adversary can achieve in our real world, could have also been achieved in the real world.

For example, for obtaining secure communication, Alice will send her message to the trusted party, who will then convey it to Bob. The adversary learns nothing about the message’s contents, nor can she change them. In the zero knowledge application, to prove that there exists some secret \(x\) such that \(f(x)=1\) where \(f(\cdot)\) is a public function, the prover Alice sends to the trusted party her secret input \(x\), the trusted party then verifies that \(f(x)=1\) and simply sends to Bob the message “the statement is true”. It does not reveal to Bob anything about the secret \(x\) beyond that.

But this paradigm goes well beyond this. For example, second price (or Vickrey) auctions are known as a way to incentivize bidders to bid their true value. In these auctions, every potential buyer sends a sealed bid, and the item goes to the highest bidder, who only needs to pay the price of the second-highest bid. We could imagine a digital version, where buyers send encrypted versions of their bids. The auctioneer could announce who the winner is and what was the second largest bid, but could we really trust him to do so faithfully? Perhaps we would want an auction where even the auctioneer doesn’t learn anything about the bids beyond the identity of the winner and the value of the second highest bid? Wouldn’t it be great if there was a trusted party that all bidders could share with their private values, and it would announce the results of the auction but nothing more than that? This could be useful not just in second price auctions but to implement many other mechanisms, especially if you are a Danish sugar beet farmer.

There are other examples as well. Perhaps two hospitals might want to figure out if the same patient visited both, but do not want (or are legally not allowed) to share with one another the list of people that visited each one. A trusted party could get both lists and output only their intersection.

The list goes on and on. Maybe we want to aggregate securely information of the performance of Estonian IT firms or the financial health of wall street banks. Almost every cryptographic task could become trivial if we just had access to a universally trusted party. But of course in the real world, we don’t. This is what makes the notion of secure multiparty computation so exciting.

We now turn to formal definitions. As we discuss below, there are many variants of secure multiparty computation, and we pick one simple version below. A \(k\)-party protocol is a set of efficiently computable \(k\) prescribed interactive strategies for all \(k\) parties. We assume the existence of an authenticated and private point to point channel between every pair of parties (this can be implemented using signatures and encryptions). A \(k\) party functionality is a probabilistic process \(F\) mapping \(k\) inputs in \({\{0,1\}}^n\) into \(k\) outputs in \({\{0,1\}}^n\).

First attempt: a slightly “too ideal” definition

Here is one attempt of a definition that is clean but a bit too strong, which nevertheless captures much of the spirit of secure multiparty computation:

Definition (MPC without aborts): Let \(F\) be a \(k\)-party functionality. A secure protocol for \(F\) is a protocol for \(k\) parties satisfying that for every \(T\subseteq [k]\) and every efficient adversary \(A\), there exists an efficient “ideal adversary” (i.e., efficient interactive algorithm) \(S\) such that for every set of inputs \(\{ x_i \}_{i\in [k]\setminus T}\) the following two distributions are computationally indistinguishable:

The tuple \((y_1,\ldots,y_k)\) of outputs of all the parties (both controlled and not controlled by the adversary) in an execution of the protocol where \(A\) controls the parties in \(T\) and the inputs of the parties not in \(T\) are given by \(\{ x_i \}_{i\in [k]\setminus T}\).

The tuple \((y_1,\ldots,y_k)\) that is computed using the following process:

We let \(\{ x_i \}_{i \in T}\) be chosen by \(S\), and compute \((y'_1,\ldots,y'_k)=F(x_1,\ldots,x_k)\).

For every \(i\in [k]\), if \(i\not\in T\) (i.e., party \(i\) is “honest”) then \(y_i=y'_i\) and otherwise, we let \(S\) choose y_i$.

That is, the protocol is secure if whatever an adversary can gain by taking complete control over the set of parties in \(T\), could have been gain by simply using this control to choose particular inputs \(\{ x_i \}_{i\in T}\), run the protocol honestly, and observe the outputs of the functionality.

Note that in particular if \(T=\emptyset\) (and hence there is no adversary) then if the parties’ inputs are \((x_1,\ldots,x_k)\) then their outputs will equal \(F(x_1,\ldots,x_k)\).

Allowing for aborts

The definition above is a little too strong, in the following sense. Consider the case that \(k=2\) where there are two parties Alice (Party \(1\)) and Bob (Party \(2\)) that wish to compute some output \(F(x_1,x_2)\). If Bob is controlled by the adversary then he clearly can simply abort the protocol and prevent Alice from computing \(y_1\). Thus, in this case in the actual execution of the protocol the output \(y_1\) will be some error message (which we denote by \(\bot\)). But we did not allow this possiblity for the idealized adversary \(S\): if \(1\not\in S\) then it must be the case that the output \(y_1\) is equal to \(y'_1\) for some \((y'_1,y'_2)=F(x_1,x_2)\).

This means that we would be able to distinguish between the output in the real and ideal setting. This motivates the following, slightly more messy definition, that allows for the ability of the adversary to abort the execution at any point in time:

Definition (MPC with aborts): Let \(F\) be a \(k\)-party functionality. A secure protocol for \(F\) is a protocol for \(k\) parties satisfying that for every \(T\subseteq [k]\) and every efficient adversary \(A\), there exists an efficient “ideal adversary” (i.e., efficient interactive algorithm) \(S\) such that for every set of inputs \(\{ x_i \}_{i\in [k]\setminus T}\) the following two distributions are computationally indistinguishable:

The tuple \((y_1,\ldots,y_k)\) of outputs of all the parties (both controlled and not controlled by the adversary) in an execution of the protocol where \(A\) controls the parties in \(T\) and the inputs of the parties not in \(T\) are given by \(\{ x_i \}_{i\in [k]\setminus T}\) we denote by \(y_i = \top\) if the \(i^{th}\) party aborted the protocol.

The tuple \((y_1,\ldots,y_k)\) that is computed using the following process:

We let \(\{ x_i \}_{i \in T}\) be chosen by \(S\), and compute \((y'_1,\ldots,y'_k)=F(x_1,\ldots,x_k)\).

For \(i=1,\ldots,k\) do the following: ask \(S\) if it wishes to abort at this stage, and if it doesn’t then the \(i^{th}\) party learns \(y'_i\). If the adversary did abort then we exit the loop at this stage and the parties \(i+1,\ldots,k\) (regardless if they are honest or malicious) do not learn the corresponding outputs.

Let \(k'\) be the last non-abort stage we reached above. For every \(i\not\in T\), if \(i \leq k'\) then \(y_i =y'_i\) and if \(i>k'\) then \(y'_i=\bot\). We let the adversary \(S\) choose \(\{ y_i \}_{i\in T}\).

Here are some good exercises to make sure you follow the definition:

Let \(F\) be the two party functionality such that \(F(H\|C,H')\) outputs \((1,1)\) if the graph \(H\) equals the graph \(H'\) and \(C\) is a Hamiltonian cycle and otherwise outputs \((0,0)\). Prove that a protocol for computing \(F\) is a zero knowledge proof system for the language of Hamiltonicity.

Let \(F\) be the \(k\)-party functionality that on inputs \(x_1,\ldots,x_k \in {\{0,1\}}\) outputs to all parties the majority value of the \(x_i\)’s. Then, in any protocol that securely computes \(F\), for any adversary that controls less than half of the parties, if at least \(n/2+1\) of the other parties’ inputs equal \(0\), then the adversary will not be able to cause an honest party to output \(1\).

Amazingly, we can obtain such a protocol for every functionality:

Theorem (“Fundamental theorem of cryptography”, Yao ’82, Goldreich-Micali-Wigderson ’87,…): Under reasonable assumptions for every polynomial-time computable \(k\)-functionality \(F\) there is a polynomial-time protocol that computes it securely.

There is in fact not a single theorem but rather many variants of this fundamental theorem obtained by great many people, depending on the different security properties desired, as well as the different cryptographic and setup assumptions. Some of the issues studied in the literature include the following:

Fairness, guaranteed output delivery: The definition above does not attempt to protect against “denial of service” attacks, in the sense that the adversary is allowed, even in the ideal case, to prevent the honest parties from receiving their outputs.

As mentioned above, without honest majority this is essential for simlar reasons to the issue we discussed in lecture 7 on bitcoin why achieving consensus is hard if there isn’t a honest majority. When there is an honest majority, we can achieve the property of guaranteed output delivery, which offers protection against such “denial of service” attacks. Even when there is no guaranteed output delivery, we might want the property of fairness, whereas we guarantee that if the honest parties don’t get the output then neither does the adversary. There has been extensive study of fairness and there are protocols achieving variants on it under various computational and setup assumptions.

The many variants of multiparty secure computation: This is just one simple definition and many variants have been studied in the literature. These include different network models (e.g., a broadcast channel, non-private networks, and even no authentication), different setup assumptions (e.g., public key infrastructure, common reference string, “plain vanilla” no setup, and more), different adversarial powers (e.g., computationally unbounded, bounded and malicious, “honest but curious”, “covert”), limits on adversary’s ability to control parties (e.g., honest majority, smaller fraction of parties or particular patterns of control, adaptive vs static corruption).

In particular, the definition displayed above are for standalone execution which is known not to automatically imply security with respect to concurrent composition, where many copies of the same protocol (or different protocols) could be executed simultaneously. This opens up all sorts of new attacks. See Yehuda Lindell’s thesis (or this updated version) for more. A very general notion known as “UC security” (which stands for “Universally Composable” or maybe “Ultimate Chuck”) has been proposed to achieve security in these settings, though at a price of additional setup assumptions, see here and here.

Efficiency vs. generality: While this theorem tells us that essentially every protocol problem can be solved in principle, its proof will almost never yield a protocol you actually want to run since it has enormous efficiency overhead. The issue of efficiency is the biggest reason why secure multiparty computation has so far not had a great many practical applications. However, researchers have been showing more efficient tailor-made protocols for particular problems of interest, and there has been steady progress in making those results more practical. See the slides and videos from this workshop for more.

Is multiparty secure computation the end of crypto? The notion of secure multiparty computation seems so strong that you might think that once it is achieved, aside from efficiency issues, there is nothing else to be done in cryptography. This is very far from the truth. Multiparty secure computation do give a way to solve a great many problems in the setting where we have arbitrary rounds of interactions and unbounded communication, but this is far from being always the case. As we mentioned before, interaction can sometimes make a qualitative difference (when Alice and Bob are separated by time rather than space). As we’ve seen in the discussion of fully homomorphic encryption, there are also other properties, such as compact communication, which are not implied by multiparty secure computation but can make all the difference in contexts such as cloud computing. That said, multiparty secure computation is an extremely general paradigm that does apply to many cryptographic problems.

Further reading: The survey of Lindell and Pinkas gives a good overview of the different variants and security properties considered in the literature, see also Section 7 in this survey of Goldreich. Chapter 6 in Pass and Shelat’s notes is also a good source.

Example: Second price auction using bitcoin

Suppose we have the following setup: an auctioneer wants to sell some item and run a second-price auction, where each party submits a sealed bid, and the highest bidder gets the item for the price of the second highest bid. However, as mentioned above, the bidders do not want the auctioneer to learn what their bid was, and in general nothing else other than the identity of the highest bidder and the value of the second highest bid. Moreover, we might want the payment is via an electronic currency such as bitcoin, so that the auctioneer not only gets the information about the winning bid but an actual self-certifying transaction they can use to get the payment.

Here is how we could obtain such a protocol using secure multiparty computation:

- We have \(k\) parties where the first party is the auctioneer and parties \(2,\ldots,k\) are bidders. Let’s assume for simplicity that each party \(i\) has a public key \(v_i\) that is associated with some bitcoin account. We treat all these keys as the public input.

The private input of bidder \(i\) is the value \(x_i\) that it wants to bid as well as the secret key \(s_i\) that corresponds to their public key.

The functionality only provides an output to the auctioneer, which would be the identity \(i\) of the winning bidder as well as a valid signature on this bidder transferring \(x\) bitcoins to the key \(v_1\) of the auctioneer, where \(x\) is the value of the second largest valid bid (i.e., \(x\) equals to the second largest \(x_j\) such that \(s_j\) is indeed the private key corresponding to \(v_j\).)

It’s worthwhile to think about what a secure protocol for this functionality accomplishes. For example:

The fact that in the ideal model the adversary needs to choose its queries independently means that the adversary cannot get any information about the honest parties’ bids before deciding on its bid.

Despite all parties using their signing keys as inputs to the protocol, we are guaranteed that no one will learn anything about another party’s signing key except the single signature that will be produced.

Note that if \(i\) is the highest bidder and \(j\) is the second highest, then at the end of the protocol we get a valid signature using \(s_i\) on a transaction transferring \(x_j\) bitcoins to \(v_1\), despite \(i\) not knowing the value \(x_j\) (and in fact never learning the identity of \(j\).) Nonetheless, \(i\) is guaranteed that the signature produced will be on an amount not larger than its own bid and an amount that one of the other bidders actually bid for.

I find the ability to obtain such strong notions of security pretty remarkable. This demonstrates the tremendous power of obtaining protocols for general functionalities.

Another example: distributed and threshold cryptography

It sometimes makes sense to use multiparty secure computation for cryptographic computations as well. For example, there might be several reasons why we would want to “split” a secret key between several parties, so no party knows it completely.

Some proposals for key escrow (giving government or other entity an option for decrypting communication) suggested to split a cryptographic key between several agencies or institutions (say the FBI, the courts, etc..) so that they must collaborate in order to decrypt communication, thus hopefully preventing unlawful access.

On the other side, a company might wish to split its own key between several servers residing in different countries, to ensure not one of them is completely under one jurisdiction. Or it might do such splitting for technical reasons, so that if there is a break in into a single site, the key is not compromised.

There are several other such examples. One problem with this approach is that splitting a cryptographic key is not the same as cutting a 100 dollar bill in half. If you simply give half of the bits to each party, you could significantly harm security. (For example, it is possible to recover the full RSA key from only \(27\%\) of its bits).

Here is a better approach, known as secret sharing: To securely share a string \(s\in{\{0,1\}}^n\) among \(k\) parties so that any \(k-1\) of them have no information about it, we choose \(s_1,\ldots,s_{k-1}\) at random in \({\{0,1\}}^n\) and let \(s_k = s \oplus s_1 \oplus \cdots s_{k-1}\) (\(\oplus\) as usual denotes the XOR operation), and give party \(i\) the string \(s_i\), which is known as the \(i^{th}\) share of \(s\). Note that \(s = s_1 \oplus \cdots \oplus s_t\) and so given all \(k\) pieces we can reconstruct the key. Clearly the first \(k-1\) parties did not receive any information about \(s\) (since their shares were generated independent of \(s\)), but the following not-too-hard claim shows that this holds for every set of \(k-1\) parties:

Claim: For every \(s\in{\{0,1\}}^n\), and set \(T\subseteq [k]\) of size \(k-1\), we get exactly the same distribution over \((s_1,\ldots,s_k)\) as above if we choose \(s_i\) for \(i\in T\) at random and set \(s_t = s \oplus_{i\in T} s_i\) where \(t = [k]\setminus T\).

We leave the proof of the claim as an exercise.

Secret sharing solves the problem of protecting the key “at rest” but if we actually want to use the secret key in order to sign or decrypt some message, then it seems we need to collect all the pieces together into one place, which is exactly what we wanted to avoid doing. This is where multiparty secure computation comes into play, we can define a functionality \(F\) taking public input \(m\) and secret inputs \(s_1,\ldots,s_k\) and producing a signature or decryption of \(m\). In fact, we can go beyond that and even have the parties sign or decrypt a message without them knowing what this message is, except that it satisfies some conditions.

Moreover, secret sharing can be generalized so that a threshold other than \(k\) is necessary and sufficient to reconstruct the secret (and people have also studied more complicated access patterns). Similarly multiparty secure computation can be used to achieve distributed cryptography with finer access control mechanisms.

Proving the fundamental theorem:

We will complete the proof of (a relaxed version of) the fundamental theorem over this lecture and the next one. The proof consists of two phases:

A protocol for the “honest but curious” case using fully homomorphic encryption.

A reduction of the general case into the “honest but curious” case where the adversary follows the protocol precisely but merely attempts to learn some information on top of the output that it is “entitled to” learn. (This reduction is based on zero knowledge proofs and is due to Goldreich, Micali and Wigderson)

We note that while fully homomorphic encryption yields a conceptually simple approach for the second step, it is not currently the most efficient approach, and rather most practical implementations are based on the technique known as “Yao’s Garbled Ciruits” (see this book or this paper or this survey ) which in turn is based a notion known as oblivious transfer which can be thought of as a “baby private information retrieval” (though it preceded the latter notion).

We will focus on the case of two parties. The same ideas extend to \(k>2\) parties but with some additional complications.

Malicious to honest but curious reduction

We start from the second stage. Giving a reduction transforming a protocol in the “honest but curious” setting into a protocol secure in the malicious setting. Note that a priori, it is not obvious at all that such a reduction should exist. In the “honest but curious” setting we assume the adversary follows the protocol to the letter. Thus a protocol where Alice gives away all her secrets to Bob if he merely asks her to do so politely can be secure in the “honest but curious” setting if Bob’s instructions are not to ask. More seriously, it could very well be that Bob has an ability to deviate from the protocol in subtle ways that would be completely undetectable but allow him to learn Alice’s secrets. Any transformation of the protocol to obtain security in the malicious setting will need to rule out such deviations.

The main idea is the following: we do the compilation one party at a time - we first transform the protocol so that it will remain secure even if Alice tries to cheat, and then transform it so it will remain secure even if Bob tries to cheat. Let’s focus on Alice. Let’s imagine (without loss of generality) that Alice and Bob alternate sending messages in the protocol with Alice going first, and so Alice sends the odd messages and Bob sends the even ones. Lets denote by \(m_i\) the message sent in the \(i^{th}\) round of the protocol. Alice’s instructions can be thought of as a sequence of functions \(f_1,f_3,\cdots,f_t\) (where \(t\) is the last round in which Alice speaks) where each \(f_i\) is an efficiently computable function mapping Alice’s secret input \(x_1\), (possibly) her random coins \(r_1\), and the transcript of the previous messages \(m_1,\ldots,m_{i-1}\) to the next message \(m_i\). The functions \(\{ f_i \}\) are publicly known and part of the protocol’s instructions. The only thing that Bob doesn’t know is \(x_1\) and \(r_1\). So, our idea would be to change the protocol so that after Alice sends the message \(i\), she proves to Bob that it was indeed computed correctly using \(f_i\). If \(x_1\) and \(r_1\) weren’t secret, Alice could simply send those to Bob so he can verify the computation on his own. But because they are (and the security of the protocol could depend on that) we instead use a zero knowledge proof.

Let’s assume for starters that Alice’s strategy is deterministic (and so there is no random tape \(r_1\)). A first attempt to ensure she can’t use a malicious strategy would be for Alice to follow the message \(m_i\) with a zero knowledge proof that there exists some \(x_1\) such that \(m_i=f(x_1,m_1,\ldots,m_{i-1})\). However, this will actually not be secure - it is worth while at this point for you to pause and think if you can understand the problem with this solution.

.

.

(No really, please stop and think..)

.

.

.

The problem is that at every step Alice proves that there exists some input \(x_1\) that can explain her message but she doesn’t prove that it’s the same input for all messages. If Alice was being truly honest, she should have picked her input once and use it throughout the protocol, and she could not compute the first message according to the input \(x_1\) and then the third message according to some input \(x'_1 \neq x_1\). Of course we can’t have Alice reveal the input, as this would violate security. The solution is for Alice to commit in advance to the input. We have seen commitments before, but let us now formally define the notion:

Definition (commitment scheme): A commitment scheme for strings of length \(\ell\) is a two party protocol between the sender and receiver satisfying the following:

Hiding (sender’s security): For every two sender inputs \(x,x' \in {\{0,1\}}^\ell\), and no matter what efficient strategy the receiver uses, it cannot distinguish between the interaction with the sender when the latter uses \(x\) as opposed to when it uses \(x\)’.

Binding (reciever’s security): No matter what (efficient or non efficient) strategy the sender uses, if the reciever follows the protocol then with probability \(1-negl(n)\), there will exist at most a single string \(x\in{\{0,1\}}^\ell\) such that the transcript is consistent with the input \(x\) and some sender randomness \(r\).

That is, a commitment is the digital analog to placing a message in a sealed envelope to be opened at a later time. To commit to a message \(x\) the sender and reciever interact according to the protocol, and to open the commitment the sender simply sends \(x\) as well as the random coins it used during the commitment phase. The variant we defined above is known as computationally hiding and statistically binding, since the sender’s security is only guaranteed against efficient receivers while the binding property is guaranteed against all senders. There are also statistically hiding and computationally binding commitments, though it can be shown that we need to restrict to efficient strategies for at least one of the parties.

We have already seen a commitment scheme before (due to Naor): the receiver sends a random \(z{\leftarrow_R\;}{\{0,1\}}^{3n}\) and the sender commits to a bit \(b\) by choosing a random \(s\in{\{0,1\}}^n\) and sending \(y = PRG(s)+ bz (\mod 2)\) where \(PRG:{\{0,1\}}^n\rightarrow{\{0,1\}}^{3n}\) is a pseudorandom generator. It’s a good exercise to verify that it satisfies the above definitions. By running this protocol \(\ell\) times in parallel we can commit to a string of any polynomial length.

We can now describe the transformation ensuring the protocol is secure against a malicious Alice in full, for the case that that the original strategy of Alice is deterministic (and hence uses no random coins)

We will not prove security but will only sketch it here, see Section 7.3.2 in Goldreich’s survey for a more detailed proof:

To argue that we maintain security for Alice we use the zero knowledge property: we claim that Bob could not learn anything from the zero knowledge proofs precisely because he could have simulated them by himself. We also use the hiding property of the commitment scheme. To prove security formally we need to show that whatever Bob learns in the modified protocol, he could have learned in the original protocol as well. We do this by simulating Bob by replacing the commitment scheme with commitment to some random junk instead of \(x_1\) and the zero knowledge proofs with their simulated version. The proof of security requires a hybrid argument, and is again a good exercise to try to do it on your own.

To argue that we maintain security for Bob we use the binding property of the commitment scheme as well as the soundness property of the zero knowledge system. Once again for the formal proof we need to show that we could transform any potentially malicious strategy for Alice in the modified protocol into an “honest but curious” strategy in the original protocol (also allowing Alice the ability to abort the protocol). It turns out that to do so, it is not enough that the zero knowledge system is sound but we need a stronger property known as a proof of knowledge. We will not define it formally, but roughly speaking it means we can transform any prover strategy that convinces the verifier that a statement is true with non-negligible probability into an algorithm that outputs the underlying secret (i.e., \(x_1\) and \(r_com\) in our case). This is crucial in order to trasnform Alice’s potentially malicious strategy into an honest but curious strategy.

We can repeat this transformation for Bob (or Charlie, David, etc.. in the \(k>2\) party case) to transform a protocol secure in the honest but curious setting into a protocol secure (allowing for aborts) in the malicious setting.

Handling probabilistic strategies:

So far we assumed that the original strategy of Alice in the honest but curious is deterministic but of course we need to consider probabilistic strategies as well. One approach could be to simply think of Alice’s random tape \(r\) as part of her secret input \(x_1\). However, while in the honest but curious setting Alice is still entitled to freely choose her own input \(x_1\), she is not entitled to choose the random tape as she wishes but is supposed to follow the instructions of the protocol and choose it uniformly at random. Hence we need to use a coin tossing protocol to choose the randomness, or more accurately what’s known as a “coin tossing in the well” protocol where Alice and Bob engage in a coin tossing protocol at the end of which they generate some random coins \(r\) that only Alice knows but Bob is still guaranteed that they are random. Such a protocol can actually be achieved very simply. Suppose we want to generate \(m\) coins:

- Alice selects \(r'{\leftarrow_R\;}{\{0,1\}}^m\) at random and engages in a commitment protocol to commit to \(r'\).

- Bob selects \(r'' {\leftarrow_R\;}{\{0,1\}}^m\) and sends it to Alice in the clear.

- The result of the coin tossing protocol will be the string \(r=r'\oplus r''\).

Note that Alice knows \(r\). Bob doesn’t know \(r\) but because he chose \(r''\) after Alice committed to \(r'\) he knows that it must be fully random regardless of Alice’s choice of \(r'\). It can be shown that if we use this coin tossing protocol at the beginning and then modify the zero knowledge proofs to show that \(m_i=f(x_1,r_1,m_1,\ldots,m_{i-1})\) where \(r\) is the string that is consistent with the transcript of the coin tossing protocol, then we get a general transformation of an honest but curious adversary into the malicious setting.

The notion of multiparty secure computation - defining it and achieving it - is quite subtle and I do urge you to read some of the other references listed above as well. In particular, the slides and videos from the Bar Ilan winter school on secure computation and efficiency, as well as the ones from the winter school on advances in practical multiparty computation are great sources for this and related materials.